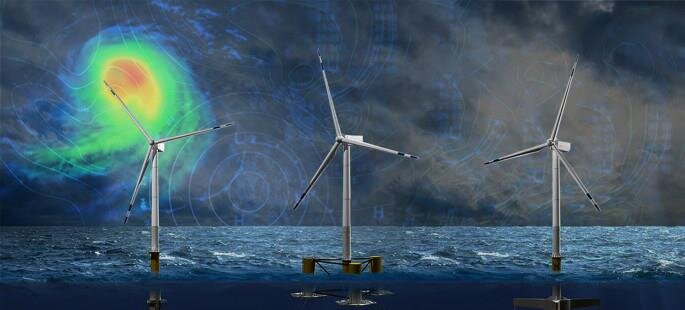

Can Offshore Wind Stop Hurricanes in Their Tracks?

By: Evan Healey

Climate change has already made hurricanes stronger. Scientists agree that as carbon dioxide from human activities accumulates in the atmosphere and oceans continue to warm, hurricanes will only further increase in severity (and possibly frequency as well). However, several years ago researchers at Stanford demonstrated that large-scale offshore wind farms are capable of significantly reducing the destructive effects of hurricanes while producing valuable renewable electricity. Not only could hurricanes be made less destructive by harvesting some of their energy, but the energy sapped from the storm by wind turbines would also be useable by consumers (who are frequently in short supply of electricity after a hurricane).

The Stanford study suggested that large-scale offshore wind farms have the potential to decrease both the peak wind speed and storm surge of hurricanes by a considerable margin. A team lead by Mark Jacobson (who is also an expert witness for the youth plaintiffs in the ongoing Juliana v. United States litigation) used computer models to run recent hurricanes Sandy, Katrina, and Isaac through several simulations that included varying levels of offshore wind development. The results were simply astounding. The models showed peak wind speeds could be reduced by over 44 meters per second (98 mph), while storm surge could be reduced by nearly 80 percent. For context, reductions of this magnitude for Hurricane Katrina would have reduced peak wind speeds from 140 mph to about 40 mph and storm surge from 11.5 feet to about 2.5 feet.

More recent studies have looked deeper into the positive potential of offshore wind farms in the context of hurricanes and have found similar results. A 2018 study using modeled simulations of Hurricane Harvey demonstrated that either large-scale or strategically positioned small-scale offshore wind farms can protect the coast from heavy rains during hurricanes. Researchers chose Hurricane Harvey for the model simulations because it dumped historic amounts of rain on southeastern Texas – as much as 60 inches in some places.

With recent hurricanes like Harvey, Sandy, and Katrina causing $125, $70, and $160 billion worth of damage, respectively, the potential benefits of deploying offshore wind could be truly immense. So why hasn’t the US begun to deploy offshore wind on a large scale? Developers of offshore wind projects have to navigate a labyrinth of federal, state, and local regulations to obtain the necessary permits to get the go-ahead to begin construction. In addition to the high potential for speed bumps in the permitting process, offshore wind projects tend to be very capital intensive. The Cape Wind Project, an offshore wind farm slated for development in Nantucket Sound was abandoned after the original price tag of $2.5 billion saw about $70 million in legal fees added to it in the wake of protracted litigation. Opponents of offshore wind projects have also cited concerns that the aesthetics of coastal areas will be diminished, and that wildlife will be damaged.

As it stands today, there are too many obstacles and too much red tape to allow for offshore wind to reach its full potential. However, as we move toward a decarbonized future, serious consideration should be given to streamlining offshore wind permitting and subsidizing renewable energy projects that create benefits beyond carbon-free energy. International leaders in offshore wind like Denmark can offer valuable insight and help the United States deploy offshore wind power in an economically viable manner. Even in today’s volatile and contentious political climate, minimizing hurricane damage and subsequent relief expenditures is hardly a partisan issue.