Invisible Emissions: The Legal Vacuum Around AI Data Centers and Their Environmental Footprint

By: Matt Scribner

Introduction

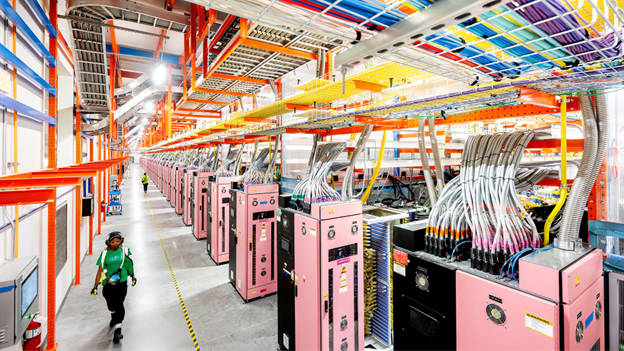

Artificial intelligence is transforming commercial, governmental, and scientific sectors at a pace unmatched by prior technological shifts. However, its rapid integration into the daily life of many Americans introduces a regulatory challenge the law is not yet prepared to manage. The core legal gap is straightforward: no federal or state regulatory framework currently requires evaluation, disclosure, mitigation, or planning for the electricity demand created by large-scale AI and data-center growth, despite the fact that these facilities are projected to reshape U.S. energy consumption within the decade. The potential environmental impacts of this shift cannot be understated.

Electricity demand from large data centers is expected to have more than double between the start of the decade and the end of 2026. Some estimates even predict that U.S. data-center load will account for more than half of the growth in electricity demand by 2030. This escalating demand collides with an already strained grid, aging transmission infrastructure, and regional reliability risks identified by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC). Despite these projections, FERC, DOE, state public utilities commissions, and other large scale regulatory bodies have failed to adopt rules requiring power-use impact assessments or binding demand-management restrictions for AI-intensive data centers.

The Regulatory Vacuum

Currently, data centers are regulated primarily as large electricity customers, not as critical infrastructure whose demand profiles directly influence grid planning, reliability, and emissions. Under the Federal Power Act, FERC oversees reliability standards and interstate transmission, but current reliability rules do not require forecasting or planning for AI-specific load growth.

While some states limit tax breaks on data centers based on clean energy performance, a lack of state level regulation is still largely present as well. State public utilities commissions exercise broad authority over utility resource planning. However, this is far too broad to effectively regulate the fast growing development of AI data centers across the nation. Even environmental review statutes, including NEPA and state level equivalents, generally focus on the environmental impacts of data-center construction, not the system-wide emissions or grid impacts caused by additional electricity consumption. The lack of comprehensive regulatory schemes on both the state and federal level is allowing electricity usage to explode as AI usage grows in popularity. Absent imminent regulatory change, the environmental consequences of unchecked electricity usage could be catastrophic.

The Climate Consequences of Unregulated AI Usage

The surge in demand for artificial intelligence, and with it the expansion of large, resource intensive data centers, is poised to impose serious environmental costs. Left unregulated, this rising demand threatens to further strain fragile power infrastructure and amplify the acceleration of climate change.

A recent empirical study of over 2,100 U.S. data centers, covering operations between September 2023 and August 2024, found that data centers already generate more than 105 million metric tons of CO₂ equivalent annually, and account for more than 4% of U.S. electricity usage overall. That emissions footprint is not a statistically insignificant figure. It represents a substantial share of national greenhouse gas output, undermining state and federal decarbonization targets. Considering that AI is in the early stages of its development and implementation, the consequences of that number expanding are scary to think about.

Further, the carbon intensity - the CO₂ emissions per unit of electricity consumed - of many data centers significantly exceeds the U.S. average. This disparity reflects the fact that many data centers are located in regions heavily dependent on fossil-fuel power plants. This creates an environmental “double whammy”, as both emissions from the electrical grid and fossil fuels become an issue. As AI-driven demand increases, even modest growth could translate into outsized emissions.

Beyond greenhouse gases, broader environmental risks exist as well. The rapid proliferation of data centers may drive increased demand for additional generation capacity, which is often fossil-fuel based. This will likely exacerbate local air and water pollution, ecosystem disruption, and resource consumption. A 2025 report by Cornell researchers estimated that, if the current rate of AI growth continues, U.S. data-center demand could add 24 to 44 million metric tons of CO₂ annually by 2030, emissions on par with adding several million additional cars on the road. That same study forecasts enormous water-use increases for cooling infrastructure, on the order of 731 to 1,125 million cubic meters of water per year, a quantity equivalent to the annual household water use of 6 to 10 million Americans.

The implications these figures could have for climate policy are severe. As new data centers ramp up, the burden on power grids could force utilities to lean more heavily on fossil-fuel generation. Without developing regulations to avoid this reality, such as binding clean energy standards specifically targeting AI and emissions accounting, AI growth could lock in decades of elevated emissions and reverse recent progress in grid decarbonization.

While global climate change will likely be significantly accelerated if unregulated growth continues into the future, Americans will also see the effects locally. Local air quality, water resources, and ecosystem health will likely suffer, particularly in communities near fossil-fuel generation or new plant siting. Unfortunately, these communities often happen to be those of lower socioeconomic status, exacerbating environmental justice issues. This points to the likely scenario that the environmental burdens of AI-driven infrastructure will disproportionately fall on vulnerable populations.

Potential Legal Pathways

While this situation seems quite dire, there are several regulatory schemes that could be put in place to curb and monitor energy usage related to artificial intelligence. One or several of the following ideas could be put in place to prevent imminent environmental catastrophe from taking place.

I. Mandatory AI Electricity Demand Disclosures

Congress, FERC, or both could require large AI developers and data-center operators to disclose projected electricity demand, similar to existing industrial reporting programs. This would allow utilities and regulators to proactively, rather than retroactively, adjust to unexpected load spikes. With transparent usage and demand data, state Public Utilities Commissions (PUCs) and regional transmission organizations could better integrate emerging load into resource planning, allocation, and grid expansion processes. This reduces the risk of delayed infrastructure and ensures costs are allocated fairly, while also aiding in preventing unregulated, widespread energy consumption from this sector.

II. Integration into Utility Resource Planning

State public utility commissions could mandate that AI-driven loads be incorporated into Integrated Resource Plans. IRPs guide utilities in planning electricity generation, transmission, and storage over multiple years, balancing supply reliability with cost and environmental goals. By including AI-driven demand, utilities could invest in sufficient generation capacity or storage solutions to handle spikes in usage. For example, an AI operator planning to double energy consumption could trigger investments in renewable energy or battery storage to offset increased demand. Integrating AI demand into IRPs ensures that grid expansion and decarbonization strategies remain coordinated and that large users contribute to system-wide sustainability. While this is not a wholesale federal regulation scheme, even statewide implementations such as this would go a long way in reducing AI based carbon emissions going forward.

III. Interconnection and Cost Sharing Rules

Regulators could attach conditions to grid interconnection agreements for large AI companies and users. These could include commitments to participate in load-shifting programs during peak periods, helping balance large scale carbon usage out with restorative practices. Without such rules, the costs of accommodating AI demand could fall unfairly on other ratepayers, when the companies creating the demand and subsequent carbon output should bear the costs. Interconnection standards ensure that data centers pay their fair share of grid improvements and incentivize operators to adopt energy-efficient practices. For example, a new AI facility might be required to deploy a battery system that can temporarily supply its own peak load, reducing strain on the broader grid.

Conclusion

The rapid growth of AI, and the corresponding electricity demand from hyperscale data centers, presents a pivotal moment in the evolution of the U.S. power system and the future of climate change. If left unaddressed, the surge threatens to overwhelm transmission infrastructure, lock in long‑lived fossil-fuel generation, degrade reliability, and create widespread negative outcomes for vulnerable populations especially.

If regulators fail to act, the consequence is not just rising power bills, but rather, it is a fundamental rollback of decades of progress toward a clean, reliable, equitable energy system. But, if they act decisively, they can direct the AI boom to become a catalyst for grid innovation: one that prioritizes clean energy, demand flexibility, and long-term resilience. While we find ourselves in the “wild west” of artificial intelligence, we cannot stay in this unregulated world surrounding the new technology forever. The time for widespread regulation is now.